It's the one diagnosis that turns most sports fans into instant injury experts.

No medical degree is needed to know that "torn anterior cruciate ligament" will be accompanied by "will miss the season" somewhere in the sentence.

Torn ACLs are the most common cause of NFL players being sidelined for the entire regular season before a game has even been played. So far this offseason -- from Jacksonville Jaguars first-round pick Dante Fowler on the first day of rookie minicamp through Dallas Cowboys cornerback Orlando Scandrick on Tuesday -- 25 players have suffered torn ACLs. It happened to 22 players last offseason and 31 the year before, according to the ACL Recovery Club.

The injury often occurs without any contact, as was the case when Green Bay Packers wide receiver Jordy Nelson crumpled to the ground untouched after jumping to make what appeared to be a routine catch in Sunday's preseason game against the Pittsburgh Steelers.

"When you jump and then land or begin to run, you need both the quadriceps muscle in front of your knee and your hamstring muscles in the back of your knee to fire at exactly the same time," said Dr. Robert Klapper, the chief of orthopedic surgery at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Group in Los Angeles. "If the hamstring is a fraction of a second off in firing, as you fire the quadriceps muscle, you are literally moving the tibia forward on the femur and it snaps the ligament."

While exact recovery times fluctuate, if a player tears his ACL at any point during training camp in August, the recovery and rehab following surgery would be expected to sideline him at least through January. Even a torn ACL during OTAs in May can be a season-ender. There have been rare exceptions to the rule, but six to nine months is generally the recovery time.

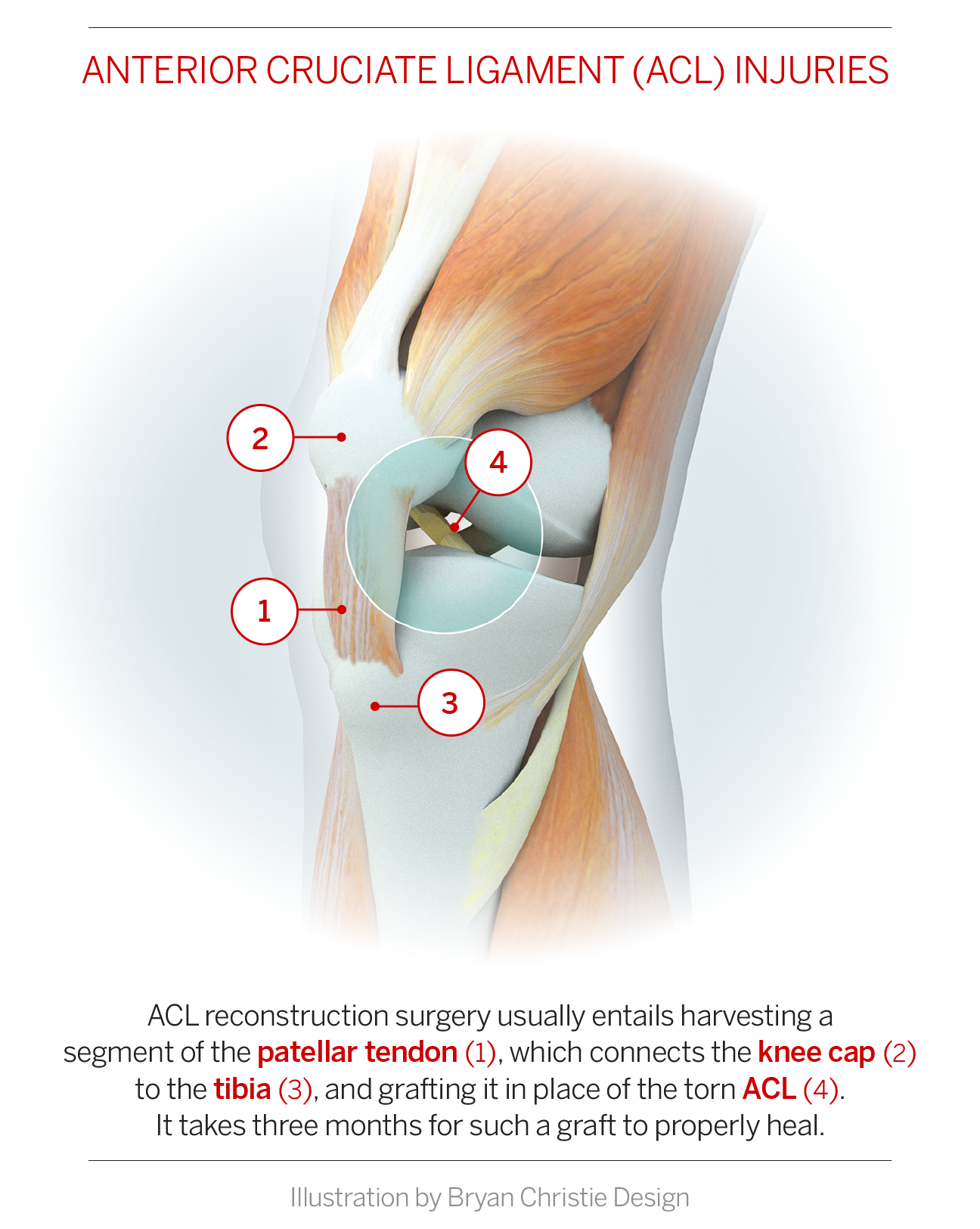

The reconstruction surgery usually entails harvesting a segment of the patellar tendon, which connects the kneecap to the tibia, and grafting it in place of the torn ACL. It takes months for the graft to properly heal.

"What we're waiting for is biology," said ESPN medical expert Dr. Mark Adickes, co-medical director of the Ironman Sports Medicine Institute at Memorial Hermann Hospital in Houston. "For an ACL not to tear, it has to be living tissue. What I'll do is take a rectangle of bone [attached to a section of the patellar tendon] out of the kneecap and then a rectangle of bone out of the tibia and that's how we make the new ACL. So you have your bone on both ends growing into your bone, and that alone takes three months. That becomes living tissue."

The surgery is only the beginning of a long road to recovery.

"After the graft matures and takes on the properties of a ligament, there's all the external stuff the player has to deal with," said Stephania Bell, a physical therapist and injury analyst at ESPN. "The player has to get their range of motion back, their strength back and they have to gradually resume their activity. You literally have to relearn how to walk, and from that you go to running and from that to a highly complex skill set which you need to play football."

While the science behind ACL injuries, surgeries and rehab can be easily explained with diagrams and knee models, the emotional and psychological recovery can be fully understood only through experience.

Darrelle Revis knows what Nelson is going through. The All-Pro New York Jets cornerback, who is three years removed from his ACL tear, feels the pain -- and a kinship -- whenever he sees another player go down with the same injury.

"It's really draining," Revis said. "When you get into the ACL family -- that's what we say, the ACL family -- that's the same thing Jordy will go through. A lot of guys go through it. You talk to guys. You talk to past players who had it. You talk to present players. You talk about the process you have to go through, the rehab."

After Revis went down in the third game of the 2012 season, he stopped traveling with the team. He eventually took his rehab to a facility in Arizona and could watch games only on TV as the Jets struggled through a 6-10 season.

"It's a dark place because the rehab is pretty tough on a day-to-day basis," Revis said. "Sometimes you might think you're not doing enough for that day, and that's something you have to fight through."

Revis initially made the same mistake many members of the ACL family encounter. They treat recovering from an ACL surgery like other injuries, but it's really unlike anything else they have been through. They can't significantly speed up ACL recovery time by working harder in rehab.

"Some days you might feel you're not doing enough because you're so competitive as a player and you're anxious to get back and recover from the injury," Revis said. "It takes a little patience. It's the competitiveness you have as an NFL player."

That's one of the challenges medical professionals face, according to noted orthopedic surgeon Dr. James Andrews.

"My goal as a physician along with the other sports doctors is not to see how fast we can get them back," Andrews said, "but getting them fully well and making sure they come back safely."

To minimize the risk of reinjury, doctors have to make sure their ACL patients understand that both hard work and patience are necessary for a successful recovery.

"You can get your muscle back," Andrews said, "but the ligament still has to go through a maturation process. They don't understand all that, but you just keep telling them you can't bargain with Mother Nature. You can push Mother Nature, but you can't bargain with Mother Nature and turn it around to suit your needs."

Von Miller didn't want to believe it.

After totaling 30 sacks for the Denver Broncos in his first two NFL seasons, the outside linebacker was suspended for the first six games of the 2013 season for violating the league's substance-abuse policy. He looked like his old self upon his return, but in Week 16 against the Houston Texans, Miller collapsed to the ground after fighting off a block midway through the first quarter.

"When they first told me, I was in denial," Miller said. "I was like 'Nah, that's not me.' ... I [thought] I just sprained it for the longest time. When I sat down with the trainers and the doctors and they told me the tests showed I tore my ACL, I was like, at that point in that year, 'What else can possibly go wrong?'

"I was right in that bad spot for about five minutes, I cried for about five minutes. Some teammates came over, and right then I told myself that's a wrap on feeling bad, that right then I was going to go at it."

Andrews said players know what it means when they are told they have a torn ACL, and a reaction like Miller's is typical for a pro athlete.

"They know they have a long year or year and half ahead of them," Andrews said. "They also know they can get well and get back to playing. It's all a positive attitude once they get through the initial reaction. They're down in the dumps for about 24 hours and then most of them, being who they are, prop back up and are ready to get going and ready to get it done."

When players are able to begin the process of rehabbing, they can lose their connection to the rest of the team. Rehabbing players usually arrive at the training facility around 7 a.m. and finish before their teammates arrive. Some will stay and sit in on team meetings and watch practice, trying to retain some semblance of normalcy during their lost season. But the inability to play, practice, travel to road games or even stand on the sidelines can be a reality check.

"The loneliest feeling," Miller said, "is right when you get done with your rehab, when you leave the facility and you go home at night. ... When you're doing rehab, you've got guys motivating you, you're around them, you're working hard, you feel good, you're making some progress, you're determined to get your leg back right, whatever it is you're determined to get it back right. But when you get home, get in the bed, then you think about what a long road it is that you still face.

"You're just there and it's quiet, and you just see what you're facing, that it isn't going to be some two-, three-week thing. You just put your head down and grind."

Just two days after signing a three-year, $50 million deal with the Cardinals last season, Carson Palmer tore his left ACL in the fourth quarter of a win over the St. Louis Rams that gave Arizona the best record (8-1) in the league. The Cardinals would end up going 3-4 the rest of the regular season before losing a wild-card game to the Carolina Panthers. Palmer watched every one of those games, and it has fueled a performance during this month's training camp that some are saying might be the best of his career.

"Early on right after the surgery I was not supposed to be up standing on it and walking around," said Palmer, who went through the process a second time after tearing his right ACL in 2006. "So I was in doing a lot of rehab and wasn't able to fly or travel or be on the sideline with crutches and in people's way. You're there for as much as you can and then rehab. If rehab was an hour I'd be around a lot more, but rehab was hours each day."

The long rehab process becomes a grind both physically and mentally.

"It's not only rehabilitating what's hurt, but rehabilitating the person," Miller said. "It will show what type of character you have to work your way from whatever you need to work your way back from. ... When you're rehabbing, you just have to get it done. You could do it early, you could do it late, so it might be easy to get in that habit of going later and later or whatever. Maybe you don't do all the reps as hard as you should. It's easy to fall into the trap. I wanted to make myself get there early, get going. I wanted to fight it out."

Three weeks after Miller's injury, cornerback Chris Harris Jr. went down with a torn ACL in the Broncos' divisional playoff win against the San Diego Chargers. As devastating as those injuries were to a team that would ultimately lose to the Seattle Seahawks in the Super Bowl, it gave the defensive teammates an opportunity to rehab together. The feeling of solitude many players experience during ACL rehab was replaced by a healthy competition between two athletes trying to get back on the field as quickly as possible.

"If we had to be here at 7 [a.m.], Chris was going to be here at 6:30," Miller said. "And me being a competitor, then I wanted to be here at 6:25, maybe 6:20, because I wanted to already be in my workout when he got here. We had the same plan, we were on the same week, we were doing the same squats. ... Wake up at 6 every day in rehab. Me and Chris grinding together, we looked at our times, our work, we pushed each other."

Harris thinks going through his rehabilitation with Miller enabled them to return quicker -- and maybe better than before.

"I mean, that's a bad, bad thing to happen," Harris said, "but it really helped us take that next leap on the field and off the field. Ever since he tore that ACL and came back from that rehab, [Miller] has been a totally different person in the building."

Harris, who entered the league in 2011 as an undrafted free agent, came back strong with his first Pro Bowl season in 2014 and earned a five-year, $42.5 million contract extension.

"I could have done it if I was the only one," Harris said of going through the rehab process, "but ... maybe I wouldn't have done it as fast and maybe he wouldn't have done it as fast. Shows you there's good in everything maybe and you just have to see it."

Miller returned with 14 sacks in 2014 and is due for a big payday as he heads into the final season of his contract.

"I'm super proud of myself, not just coming back from the injury, but that whole year," Miller said. "I mean, people don't give you a trophy when you handle things in your life and I know I still have a lot to work to handle, but I know now if I really put my mind to something I can get it done.

"I made a decision that day they told me my ACL was torn, that I was going to re-invent myself, I wasn't going to come back the same guy. I didn't know how it was going to go, but I wanted to be better, a better person, a better player with a better knee. I wanted to change myself for the better."

ESPN staff writers Rich Cimini, Jeff Legwold and Josh Weinfuss contributed to this report.