This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity. This is the English translation of the original German version. Lesen Sie diesen Text auf Deutsch.

ZEIT ONLINE: Professor Freyberger, you conduct research into the use of performance-enhancing drugs in East Germany. Why is that an important issue?

Harald Freyberger: We're talking here about a significant group of victims that many are unaware of, a group that is afflicted by immense psychological and physical suffering. And both the group and the adversity they face is growing.

ZEIT ONLINE: What have you learned?

Freyberger: On average, victims of East German doping die 10 to 12 years earlier than the rest of the population. And here's another alarming statistic: A victim of East German doping falls ill 2.7 times as often, and for psychological illnesses, we have calculated a factor of 3.2. Against this background, calls to legalize performance-enhancing drugs are naïve and irresponsible.

ZEIT ONLINE: Doping has taken place, and continues to take place, in a lot of countries. What is so special about East Germany?

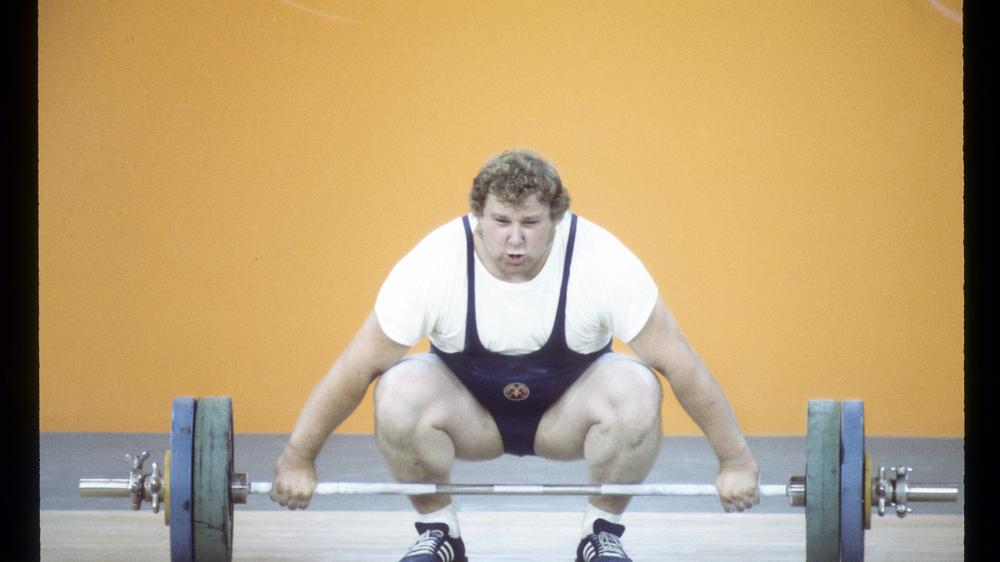

Freyberger: The magnitude in East Germany was likely unique. Unbeknownst to them, the athletes were given heavy anabolic steroids along with sex and growth hormones, often in extremely high doses. For many of the victims, the consequences have been dramatic, some of which are only appearing now, decades later.

ZEIT ONLINE: There are files assembled by the East German secret police, the Stasi, proving that doping took place, but it's not always possible to determine who received how many tablets and injections and when they took them. Nor is it always easy to determine what was given to the athletes. Given that background, how is it possible to arrive at scientifically sound conclusions?

Freyberger: In individual cases, it isn't, in fact, always possible to confirm all the details. Not everyone was affected to the same degree. But on the whole, it is possible to ascertain beyond any doubt the presence of serious health consequences. All systems of the body are affected: the heart, kidneys, skin, bones and sexual organs. Many victims suffer from depression or eating disorders and roughly every third is traumatized. In addition, outrageous doses of pain medication were administered in East Germany. That makes possible extremely intense – and thus damaging – training sessions. We have also observed social failure, occupational limitations and poverty. In the final analysis, sports in East Germany substantially worsened the lives of many.

ZEIT ONLINE: In its eagerness to win as many medals as possible, the East German regime even resorted to giving performance-enhancing drugs to children. Without their knowledge, of course, nor that of their parents.

Freyberger: That's the worst part about it. In extreme cases, the children were only 7 years old. In some places, this chemical abuse was combined with psychological or sexual abuse at the hands of doctors or trainers. Some victims have spoken of violence. Some of them didn't get any support from their parents, which multiplied their suffering. And then there is the issue of eating. Many gymnasts, for example, were pressured by their trainers to lose weight while weightlifters had to gain weight. Those were all encroachments into the natural developmental process.

The life expectancy of East German doping victims is reduced by up to 12 years

ZEIT ONLINE: You also conduct research into second generation victims. Some researchers doubt that health problems triggered by performance-enhancing drugs can be passed down to one's children – unless the doping took place during pregnancy. What is your view?

Freyberger: Such objections tend to come from biologists and pharmacologists. But they are overlooking something. The sciences of psychology and forensic psychiatry recognize the phenomenon of transgenerational trauma transmission: Traumatic experiences can be passed along to the children. From research conducted into other victim groups that suffered a similar fate, we know that the transgenerational transmission of trauma leads to the handing down of specific symptoms and can go hand in hand with significant risks – not just psychological and social, but also genetic.

ZEIT ONLINE: Many illnesses cannot be cured. Many doping victims can no longer work full time, or they can't work at all, even though they haven't even turned 50 yet. What can be done to help them?

Freyberger: Medical treatment and therapy needs to be improved. Doctors need additional training, as do psychiatrists. Only very few are familiar with the issue. Sometimes, patients must travel 500 kilometers by train to find a good doctor. And aside from a few exceptions, politicians have left the victims to their own devices. Lawmakers issued one-time damage payments of 10,500 euros to many victims. That is a good start, but when compared to the damage done, it is only a symbolic gesture.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity. This is the English translation of the original German version. Lesen Sie diesen Text auf Deutsch.

ZEIT ONLINE: Professor Freyberger, you conduct research into the use of performance-enhancing drugs in East Germany. Why is that an important issue?

Harald Freyberger: We're talking here about a significant group of victims that many are unaware of, a group that is afflicted by immense psychological and physical suffering. And both the group and the adversity they face is growing.