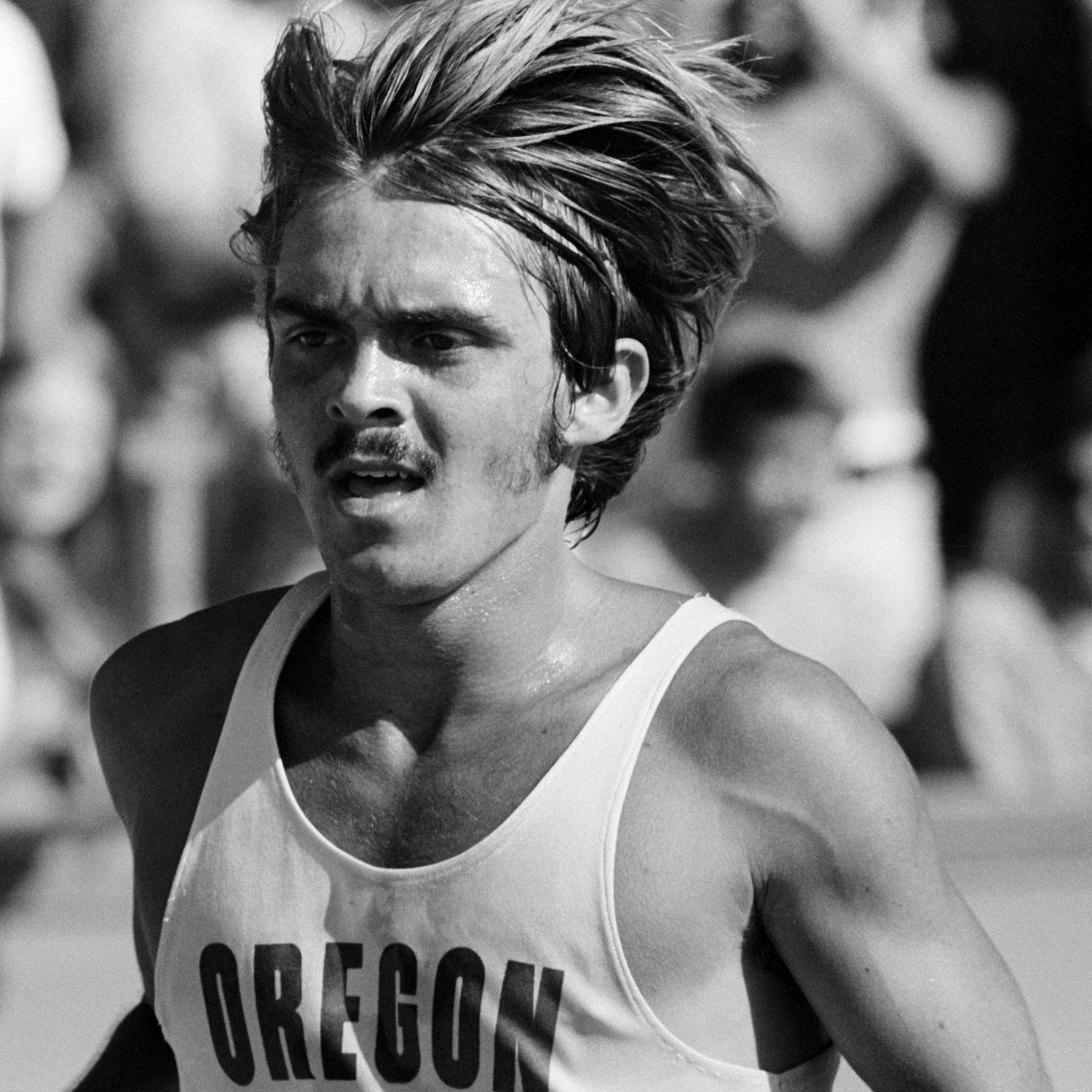

May 30, 2017, marks 42 years since the death of Steve Prefontaine, the charismatic Oregonian sometimes referred to as the “James Dean of track and field.” Like his Hollywood counterpart, Pre died in a car crash at age 24—an early exit that probably did more to secure his legend than an Olympic triumph ever would have. The site of the accident, known as Pre’s Rock, has become a repository of distance-running dreams: Fans visit from all over the world and leave behind tribute items (personal notes, track spikes, medals) for the man who once said, “I like to make something beautiful when I run. It’s more than just a race, it’s style.”

Prefontaine was never short on style. It wasn’t just the killer mustache. Whether exhibited in the defiant stance he took against the Amateur Athletic Union (the organization that determined Olympic eligibility for track and field athletes until 1978) or his brazen, front-runner approach to racing, Pre had attitude out the wazoo. Despite the fact that he never won an Olympic medal, and even though all his records have long been eclipsed, Pre remains the most celebrated runner in American history. It’s not hard to figure out why. As Alberto Salazar once put it, “He made running cool.”

Will somebody make running cool again? More than four decades after his death, the sport is still waiting for the next Steve Prefontaine.

I wouldn’t hold my breath.

Professional distance runners are generally not known for flamboyance. Indeed, fans will eat up any morsel of eccentricity they can get. (At the men’s Olympic Trials 10K last summer, Noah Droddy, the last-place finisher, became an instant sensation just because he had long hair, shades, and a backwards hat.) The only track and field athlete who might exude Prefontaine levels of bravado is Usain Bolt, and he has the distinction of being the greatest sprinter who ever lived. On the distance-running end of the spectrum, even the most dominant actors are far more subdued. Olympic marathon champion Eliud Kipchoge is a model of stoic impassivity. The wildest thing Mo Farah does is the Mobot, basically an abridged version of the “YMCA” choreography.

Perhaps this shouldn’t come as a surprise. After all, elite-level endurance sports require endless hours of solitary training and hence might be more likely to attract individuals who are okay with spending a lot of time in their own heads. Such folks typically aren’t the Rob Gronkowskis of the world. Evan Jager, the Olympic silver medalist in the steeplechase, once told me that his sport required a different mentality than athletic pursuits where, as he put it, you’re often “surrounded by a locker room full of other dudes.”

“Track and field, it doesn’t bring out nearly as many brash athletes as say, football or basketball. I think it’s a culture thing,” Jager said. “Maybe it could help the sport if everyone was a lot more brash. But there are a lot of really good people in the sport of track and field…you’re just constantly surrounded by good people, which is really nice.”

Sports, however, are about entertainment, and “niceness” is a tough sell. Not that track and field should resort to the chair-smashing tactics of the WWE, but some degree of conflict is necessary to attract and sustain the interest of a prospective audience. Pre provided that with his audacious self-belief and proclamations like, “I’m going to work so that it’s a pure guts race at the end, and if it is, I am the only one who can win it.” In footage of the men’s 5,000-meter final at the 1972 Olympics in Munich, the British commentator notes that Pre is “almost a cult in the United States, a sort of athletic Beatle.” Given the anemic viewership ratings of professional running in this country, the notion that a pro runner would have Beatle-like status feels about as plausible as Mitch McConnell functioning as master of ceremonies at Burning Man.

Sports are about entertainment, and “niceness” is a tough sell.

“Track is full of the absolute nicest and most polite athletes in all of sports, and where does it get us?” lamented Malcolm Gladwell, journalist and noted track fan, in 2015. “Jenny Simpson loses her shoe in the women’s fifteen hundred, with a lap and a half to go, destroying her chances to repeat as world champion, and she gives the most gracious interview afterward about how she’s had a wonderful career already. Great for Jenny Simpson. Bad for the sport! We need drama!”

Agreed. Though we should be careful what we wish for. Not all drama is equally desirable (see: doping scandals), and in sports, as anywhere else, there’s a fine line between having charisma and just being an idiot. Eliud Kipchoge may be reserved, but he represents the epitome of graciousness, what a British sportscaster might refer to as “class.” (Who would you rather have as an ambassador for your sport? Kipchoge or Ryan Lochte?)

Beyond any standards of athlete (mis)behavior on or off the track, there’s perhaps a more fundamental reason why a second coming of Prefontaine is unlikely. The professional athlete landscape is very different in 2017 than it was in 1972. In Pre’s day, the very definition of what it meant to be a professional was at the heart of the debate, as antiquated rules of amateurism forced several elite runners like Pre to choose between maintaining their Olympic eligibility and earning a living as an athlete. Prefontaine was as outspoken as anyone about the hypocrisy in this, and his frequent clashings with the AAU were as essential to his rebel persona as was the fact that, as running exploded in popularity across the country, the best runner in American history was living in a trailer and occasionally subsisting on food stamps. It’s a state of affairs that is unthinkable in today’s hypermonetized world of pro sports. There’s an obvious sense in which things have changed for the better, but the era of the blue-collar international sports star has been over for a long time.

That’s not to suggest that being a track and field athlete in 2017 is a lucrative profession or that these men and women don’t have to contend with bureaucratic injustice. A 2012 USA Track and Field Foundation report made headlines when it revealed that the majority of top American track athletes made less than $15,000 a year from their sport. Restrictive rules on promoting one’s sponsors during major events like the Olympics can prevent athletes from capitalizing financially during the brief period when they enjoy greater exposure. The latter issue has long been a thorn in the side of Nick Symmonds, the American 800-meter runner who has most conspicuously taken up Pre’s mantle as gleeful provocateur and critic of the sport’s governing bodies.

But a star of Pre’s caliber—who at the time of this death held every American record from 2,000 to 10,000 meters—would likely be above the fray in today’s running landscape. He would be one of hundreds of Nike-sponsored athletes with an Instagram account touting the company’s latest products. He might even have his own version of the Mobot.

Which is all fine and good. It’s just not very James Dean.