It Doesn’t Matter If Anyone Exists or Not

What a website that generates infinite fake humans tells us about modern life

You encounter so many people every day, online and off-, that it is almost impossible to be alone. Now, thanks to computers, those people might not even be real. Pay a visit to the website This Person Does Not Exist: Every refresh of the page produces a new photograph of a human being—men, women, and children of every age and ethnic background, one after the other, on and on forever. But these aren’t photographs, it turns out, though they increasingly look like them. They are images created by a generative adversarial network, a type of machine-learning system that fashions new examples modeled after a set of specimens on which the system is trained. Piles of pictures of people in, images of humans who do not exist out.

It’s startling, at first. The images are detailed and entirely convincing: an icy-eyed toddler who might laugh or weep at any moment; a young woman concerned that her pores might show; that guy from your office. The site has fueled ongoing fears about how artificial intelligence might dupe, confuse, and generally wreak havoc on commerce, communication, and citizenship.

But are these people who don’t exist any different, really, from all the Tinder profiles on which you swiped left, or the faces in the crowd on the subway whom you might never see again? Modernity—the historical period roughly but not exactly contemporaneous with the rise of industrial societies—invented anonymity and erasure, mustering sorties of human faces at one another every day. Contemporary individuals have trained all their lives to treat people in exactly this instrumental way—not only the strangers on city streets, but also the models in the photos that grace IT-solutions banners inside airport terminals, the youth of all skin shades draped across college quads on application mailers, the baristas who hand over one-Splenda soy lattes with names misspelled on the cups.

The internet has made it worse, by evaporating physical bodies into digital phantoms and then pressing them into ever-denser slums of infinite scrolling. The sheer profusion of actors online has foreclosed their need to be real at all: the armies of bots and the Russian sockpuppets, the corporate tweeps and the AI deepfakes. One can just as easily get into a heated dispute with a bot account generating random replies, or with an automated customer-service agent matching inputs to outputs, as with a human foe who is frantically tapping words into a glass rectangle.

Humankind has remedied the shock of modern life with pleasures from its reverberations. It is telling that the early commercial applications of AI similar to This Person Does Not exist include stock photography and pornography, two domains in which the actual, lived experience of human beings are completely subordinated to their deployment as vessels for pure spectacle, banal on the one hand and lurid on the other. Whether or not someone “really exists” has been of little concern in most social contexts for 150 years. It seems quaint and facile to act as if machine learning has suddenly invented the problem.

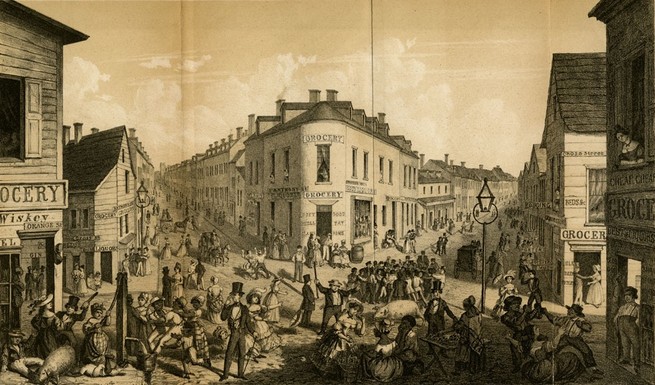

In 1863, the French poet and critic Charles Baudelaire published an essay, “The Painter of Modern Life,” in which he celebrated the power of the crowd, and of becoming lost in it. This was still a relatively new experience: The feudal cities of the Middle Ages and the mercantile ones of the Early Modern period had become larger, denser, and more diffuse. Industrialism would allow, and even force, the different classes to rub up against one another more, sometimes literally.

One major consequence of this change was that people would encounter strangers far more frequently. Initially, this was a deeply alienating experience. Compared to pastoral life, it was starling to see someone unknown, to be amid their form and even their stench, and without having chosen to do so—and then for them to vanish as quickly as they had arrived.

Baudelaire’s solution embraced the new horror of urban life as delight. The dandy and the flâneur (a “wanderer”) became his paradigms for this process. Instead of being shocked, these “perfect spectators” would choose to “become flesh with the crowd.” They would indulge, and even manufacture, the “immense joy” of “the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite.” For Baudelaire, the experience of sipping from the myriad fountains of modern anonymity offered “an immense reservoir of electrical energy.” Instead of fighting alienation, the modernist would embrace it, transforming fleeting experience into lasting vitality.

Over time, the alienation associated with modern, city life only deepened in its appeal. In 1996, the writer Vivian Gornick characterized the “endlessly advancing crowd” that jostled against her in New York City as both relaxing and energizing. An overheard conversation among young professionals; a fragment of an older couple’s argument; the honks and screeches of cars and trucks; the wafting scent of food from sidewalk vendors; the barker cries of a street hawker. “The misery in my chest begins to dissolve out,” Gornick wrote. “The city is opening itself up to me.” More than 130 years after Baudelaire jostled among the top hats of Paris, the flâneur (or flâneuse) persists, extracting energy from the crowded bustle.

Back when Gornick was writing about the urbane urban life, the commercial internet was still new. In 1995, 36 percent of Americans owned computers, and only 10 percent of them used email. As human culture tried to make sense of life in the middle of a global, decentralized network, topological metaphors ruled. The internet was said to realize a “global village,” after an idea of the media theorist Marshall McLuhan from three decades prior. It was called an “information superhighway” in an effort to make its many physical couplings comprehensible.

Today, these nicknames seem retrograde, if not just plain wrong. Thinking of the online world as a place, especially a separate place, has become outmoded. The belief that online and offline spaces are separate realms has even earned its own derogatory name, digital dualism. It’s a false dichotomy, the critics hold, to construe the “virtual” and “physical” words as distinct, or of offline and online personalities as divergent. To some extent, that speaks to the power the internet has accrued in the two decades since it became commercialized. People do so much online, from work to shopping to socializing, that virtual life has colonized and become “real” life.

Yet the internet is a place where people go, and it has never ceased to be useful to think of it as one. As a place, it feels a lot like a crowded, modernist city. As it happens, that’s how some films, such as The Emoji Movie and Ralph Breaks the Internet choose to depict it: big, dense, urban expanses, which subdivide into towers and hovels representing apps, websites, and services. The global village has become a global metropolis.

There, in its crowded streets, the modernist experience recorded by Baudelaire, Gornick, and so many others breaks down. Web browsing once felt like “surfing,” to invoke another outmoded metaphor, along with the “cyberflâneur,” a very 1990s online reimagining of the 19th-century dandy. For a time, gliding across the internet in those costumes felt pleasurable. But no longer. The grimy streets of Facebook, the angry mobs of Twitter, the irritable swarm of neighbors on Nextdoor—the experience of the online crowd has long ceased to imbue energy. Mostly, it just drains it.

There are reasons for this. The delight of online life gave way to its moil, and the pleasure of online services has been eroded by their many downsides, from compulsion to autocracy. But the trouble is also partly quantitative. Even in a big, dense city like Paris or New York, there are only so many people one can encounter in Bryant Park or when alighting from the Châtelet metro stop. The physical constraints of an actual city, along with the apparatus of its built environment, put a lid on the totality of human bodies, faces, and spirits from which one might face estrangement or draw electrified energy. The young age and smoother operation of the urban environment helped, too. Today, Gornick’s successors might tweet similar sentiments glorifying the energy of the New York City crowds, but they’d just as likely lament the endless volumes of that throng, thanks to the increasingly inoperative subway.

The flâneur was always a bit of a creeper, too. One of Baudelaire’s most famous poems, “To a Woman Passing By,” typifies how. In it, a man catches the briefest glance of a woman on the street. She is entering a carriage, dressed for mourning (and therefore potentially available); their eyes meet and then withdraw—a whole life suggested, then plucked away. “I could have loved you,” Baudelaire wrote (as I’d translate it), “And you, you knew it too.”

The chance encounter is an experience no less common to the urbanite of 2020 than to the dandy of 1863, immortalized in the “missed connections” personals sections of alt-weeklies now defunct. But it’s also presumptive, the encounterer drawing invigorating energy from a counterpart who did not consent to the affair. Still common on trains or elevators, those encounters have also burgeoned online, where easy access makes it easy to assume that the people one encounters are there for you, that they owe you a reply, or a redress, or a sex act, or worse.

Capitalism has always transformed people into latent resources, whether as labor to exploit for making products or as consumers to devour those products. But now, online services make ordinary people enact both roles: Twitter or Instagram followers for conversion into scrap income for an influencer side hustle; Facebook likes transformed into News Feed-delivery refinements; Tinder swipes that avoid the nuisance of the casual encounters that previously fueled urban delight. Every profile pic becomes a passerby—no need for an encounter, even.

In his time, Baudelaire’s response was an ethereal one. He hoped to map the patterns of the world to those of the spirit, in a doctrine of “correspondences.” The dandy, the flâneur, even the creeper weren’t solutions so much as doomed attempts to make do, for a time—as a stopgap, not a permanent remedy, which is how the doctrine was inadvertently received. One hundred and thirty years hence, Gornick was still galvanizing her routine by cannibalizing the troubled energy of her fellow city dwellers.

A quarter of a century later still, you and I and everyone else fashion the scraps of images and symbols, the physical exhaust of industrialism having given way to the symbolic exhaust of the information economy. The crowd isn’t made up of people anymore, but of pictures that might be people, of corporate brands impersonating them, of young people dancing politically in TikToks, of tweets about youths in TikToks, of disputes absent referents, of bots shouting into the void. Cacophony, an ever-amassing crowd awaiting a train that will never come.

There is no escaping this city of the internet, no flying the coop for its proverbial countryside, no respite from the constancy of its jostling beings, its barrage of images, its discharge of new distresses. But here, today, a century and a half later, armed with all of humanity’s knowledge in your palm and the latent confrontation with its billions of members, maybe the least you can do is to stop believing that you like it.

Solutions are difficult to imagine because few really want them. It is convenient—and probably necessary—not to have to know who makes your sandwich, or ever to see them again. It is still tempting to translate a glance into a fantasy. It remains essential, to some extent, to refuse engaging with the entire being of all the hundreds of individuals you might perceive every day, lest you go mad from the attempt to address them all with deep respect. Refreshing the page of people who do not exist only irritates that sore. You know you don’t need to care about them, but that’s not because they are generated by a computer. It’s because you already have had so much practice.